JNIM — Strategic Threat Outlook | November 2025

Operational Trends, Risk Assessment, and Forecast

Executive Intelligence Summary

Jama’at Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin (JNIM) remains one of the most significant jihadist threats in the Sahel and increasingly along the coastal West African corridor.

The group continues to demonstrate:

sustained operational capability across Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger;

expanding pressure towards Benin and Togo;

Strategic alignment with al-Qaeda’s regional objectives.

While no abrupt escalation is observed in November 2025, current activity patterns suggest a persistent and adaptive threat, with potential for geographic spillover and sustained instability over the next 3–6 months.

Threat level: High

Trend: ↑ (gradual expansion)

Primary risk areas: Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger; emerging pressure on Benin and Togo

Time horizon: 3–6 months

Confidence level: Medium–High

Scope and Methodology

This Strategic Threat Outlook is based on:

systematic monitoring of jihadist propaganda (videos, photos, statements, claims);

reporting from sources in the field;

OSINT, IMINT, SOCMINT, and Digital HUMINT integration.

Sources include primary JNIM media channels, open-source reporting, official statements, and local sources.

Limitations

Incomplete or delayed reporting from conflict areas;

exaggeration or omission in group claims;

Potential propaganda bias and disinformation.

Where verification is not possible, this is explicitly noted.

Overview and Security Threat Assessment

The operating environment in Mali and across the central Sahel remains characterised by persistent governance deficits, chronic socioeconomic vulnerability, and uneven state presence. These structural conditions, long evident in northern Mali and historically exploited by autonomy-oriented and separatist movements, continue to constitute the primary enabling factors for armed mobilisation. In this context, jihadist recruitment is less a function of large-scale ideological adherence than of the ability to convert local grievance systems into mechanisms of compliance, protection, and mobilisation. Where the state is absent, predatory, or inconsistent, armed actors capable of imposing order, resolving disputes, and regulating daily life retain a decisive advantage. This dynamic, widely documented in international analytical and academic literature on Sahelian insurgencies, remains central to understanding the durability and expansion of Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM).

JNIM remains the most capable Salafi-jihadist actor in the central Sahel. Established in March 2017 through the merger of Ansar Dine, Katibat Macina, al-Mourabitoun and AQIM’s Sahara branch, the group has evolved into a federated coalition rather than a hierarchically rigid organisation. It operates primarily in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger, while periodically extending operational pressure toward coastal states and peripheral borderlands. Analytically, JNIM is best understood as a hybrid insurgent structure combining guerrilla warfare, selective governance and political signalling. Its resilience derives from a decentralised operational architecture, strong social embedding through local intermediaries, and a pragmatic strategic culture that prioritises survivability and influence over symbolic or purely spectacular violence.

Over time, JNIM has demonstrated a consistent capacity to instrumentalise local discontent, particularly among marginalised rural populations exposed to insecurity, intercommunal violence and abuses by state or auxiliary forces. Its traction among segments of Fulani (Peul) communities in central Mali and Burkina Faso, and among Tuareg networks in the north, is better explained by political economy and security dynamics than by doctrinal mobilisation alone. Protection arrangements, dispute resolution, retaliation logics and access to livelihoods remain the primary vectors of recruitment and passive support. Where counterinsurgency responses rely on indiscriminate coercion, proxy militias or collective punishment, they tend to generate strategic blowback, accelerating recruitment and deepening JNIM’s social cover.

Multiple international assessments have repeatedly underlined that the persistence of jihadist violence in the Sahel is rooted in unresolved political and governance failures rather than ideological diffusion. Operationally, JNIM has pursued a sustained and adaptive campaign targeting civilians, national security forces, foreign militaries and, previously, UN peacekeepers. The group’s operational logic has remained broadly consistent: incrementally degrade state presence, contest transport corridors, impose costs on governance and convert insecurity into leverage. From an intelligence perspective, two developments matter more than the absolute number of attacks. First, JNIM has demonstrated an improved ability to coordinate operations across wide geographic areas within compressed timeframes, indicating maturation in communications, command and control, and tactical mobility. Second, the group has continued to diversify its tactical repertoire, increasingly integrating drones for aerial surveillance and attack facilitation, alongside persistent use of IEDs, ambushes, targeted assassinations and complex assaults against fixed military installations. Conflict monitoring organisations have noted that JNIM is now among the most active non-state adopters of drone-enabled tactics in the Sahelian theatre, reflecting rapid learning and diffusion within the network.

Leadership dynamics further shape JNIM’s operational behaviour across sub-theatres. While the coalition maintains strategic coherence, different operational styles remain evident. In northern Mali, leadership associated with Iyad Ag Ghali has historically prioritised calibrated violence, elite brokerage and selective accommodation with local power brokers, including militia, political and religious figures. In contrast, Amadou Koufa’s operational influence in central Mali and Burkina Faso has relied more heavily on community-level mobilisation and identity-linked grievance narratives, particularly among Fulani populations. These variations do not represent fragmentation, but rather a flexible adaptation to distinct sociopolitical environments under a common strategic framework.

The escalation cycle observed since mid-2023 reflects a convergence of internal confidence, expanded mobilisation narratives and favourable opportunity structures. While propaganda messaging alone does not drive operational tempo, it provides insight into intent and organisational self-perception. The broader trendline, higher operational intensity, expanding geographic reach and increasing tactical sophistication have continued into 2024 and 2025, as documented by international analytical reporting on Sahelian jihadist dynamics.

In 2025, a qualitative shift has become particularly salient: JNIM’s increasing reliance on economic warfare as a deliberate instrument of political coercion. The group has moved beyond opportunistic predation toward systematic disruption and regulation of supply chains, particularly in western Mali. Attacks against industrial facilities, infrastructure projects and artisanal mining sites have been followed by explicit threats and subsequent action targeting fuel supplies from neighbouring coastal states. The resulting interdiction of logistics corridors, especially around Kayes and Nioro, has transformed economic disruption into a mechanism of political engineering. In a country heavily dependent on imported fuel and goods, such a disruption constitutes a direct challenge to state functionality. The inability of the authorities to secure long, vulnerable road networks amplifies the impact of relatively small-scale attacks, producing cascading effects on transport, electricity generation, education and urban services. In this context, JNIM positions itself not merely as a spoiler but as a regulating authority capable of permitting, denying or conditioning access to essential flows.

As control over supply channels increases, JNIM’s governance practices become more visible and enforceable. Field reporting indicates the imposition of behavioural and social regulations in areas under its influence, including dress codes and public conduct rules, enforced through coercive means. These measures should be interpreted less as isolated ideological enforcement and more as signals of authority and rule-setting capacity. By normalising compliance and demonstrating the state’s inability to protect alternative norms, JNIM reinforces its claim to de facto governance.

JNIM’s continued operational effectiveness is closely tied to a tactical model optimised for the Sahelian environment. Small, highly mobile units using motorcycles and pick-up trucks are able to mass rapidly, strike and disperse in swarm-like manoeuvres that overwhelm static defences. These teams rely on radio and mobile communications, ground observers and increasingly drone-based surveillance to maintain situational awareness. The attack spectrum remains broad, ranging from IEDs and ambushes against convoys to targeted killings, raids on villages associated with pro-government militias, and complex assaults on bases and checkpoints using suicide vehicle bombs, indirect fire and direct assaults. This combination of mobility, decentralisation and technological adaptation continues to complicate prediction and containment efforts.

Despite contradictory official narratives from affected governments, available open-source indicators suggest that JNIM’s territorial influence and operational reach continue to expand. The coalition has demonstrated a new level of confidence by conducting operations hundreds of kilometres apart and by probing previously less affected areas in central and western Mali. Emerging activity along border corridors toward Niger, Benin and Nigeria further suggests a strategy of gradual geographic expansion rather than sudden territorial conquest.

Strategically, JNIM appears to be following a well-established insurgent trajectory: fight to gain leverage, govern to retain influence, and negotiate from a position of accumulated power. This does not imply imminent political talks, but it does indicate that the group’s centre of gravity is increasingly political rather than purely military. The most significant risk posed by JNIM today is therefore not limited to kinetic violence, but lies in the progressive erosion of state authority and the normalisation of armed governance across significant portions of the Sahel.

Activity and Operations Analysis — November 2025

Throughout November 2025, JNIM demonstrated a dual operational dynamic: strategic projection capabilities aimed at undermining state resilience and the local economy, and consolidation of a model of territorial and financial control in the rural areas of Liptako-Gourma and the central Sahel, combining conventional military tactics (ambushes, IEDs), economic predation, and social legitimisation campaigns. These dynamics should be seen as part of a coordinated effort to transform tactical advantages into political gains and lasting spheres of influence.

In Mali, the supply blockade has a political and economic impact. JNIM has intensified targeted attacks on fuel convoys bound for Bamako, destroying tankers, taking hostages, and mining key logistical routes. The goal is not simply to cause economic damage, but to produce a measurable political effect: paralysis of urban services, partial closure of schools and universities, power outages, and international pressure on the Malian authorities. This approach indicates a strategic reading of the regime’s vulnerability-legitimacy relationship, as the systematic disruption of supplies accentuates the perception of state incapacity. Operations against convoys combine local intelligence (reporting routes and times), the use of IEDs and engagement teams for seizures and fires, and an information campaign aimed at claiming the action as a punitive and legitimate measure (including through the use of propaganda in the local language and no longer only through az-Zallaqa).

Tactical effectiveness depends on the ability to control logistical support nodes and cross-border collusion/relocation networks that limit the state’s ability to protect extended routes. The supply blockade acts as strategic leverage, forcing external actors (logistics companies, embassies, multilateral partners) and national decision-makers to recalibrate political and military options (including emergency measures, calls for international support, and information restrictions by the junta), which JNIM can then capitalise on to reinforce its narrative of power and alternative governance. In Niger and Burkina Faso, there has been further operational spillover and territorial consolidation this month. Activities in Tillabéri and the Liptako-Gourma area show how JNIM exploits gaps in control between states to transfer fighters and weapons and to physically take advantage of exfiltration routes after high-impact actions. This month also saw the first claims and attacks attributed to JNIM in Nigeria, indicating a deliberate attempt to test new operational theatres and establish synergies with local actors. Although the attacks are limited in scale at present, the presence of operational links is strategically significant: it provides JNIM with access to markets, routes, and extortion opportunities in relatively vulnerable and politically fragmented contexts.

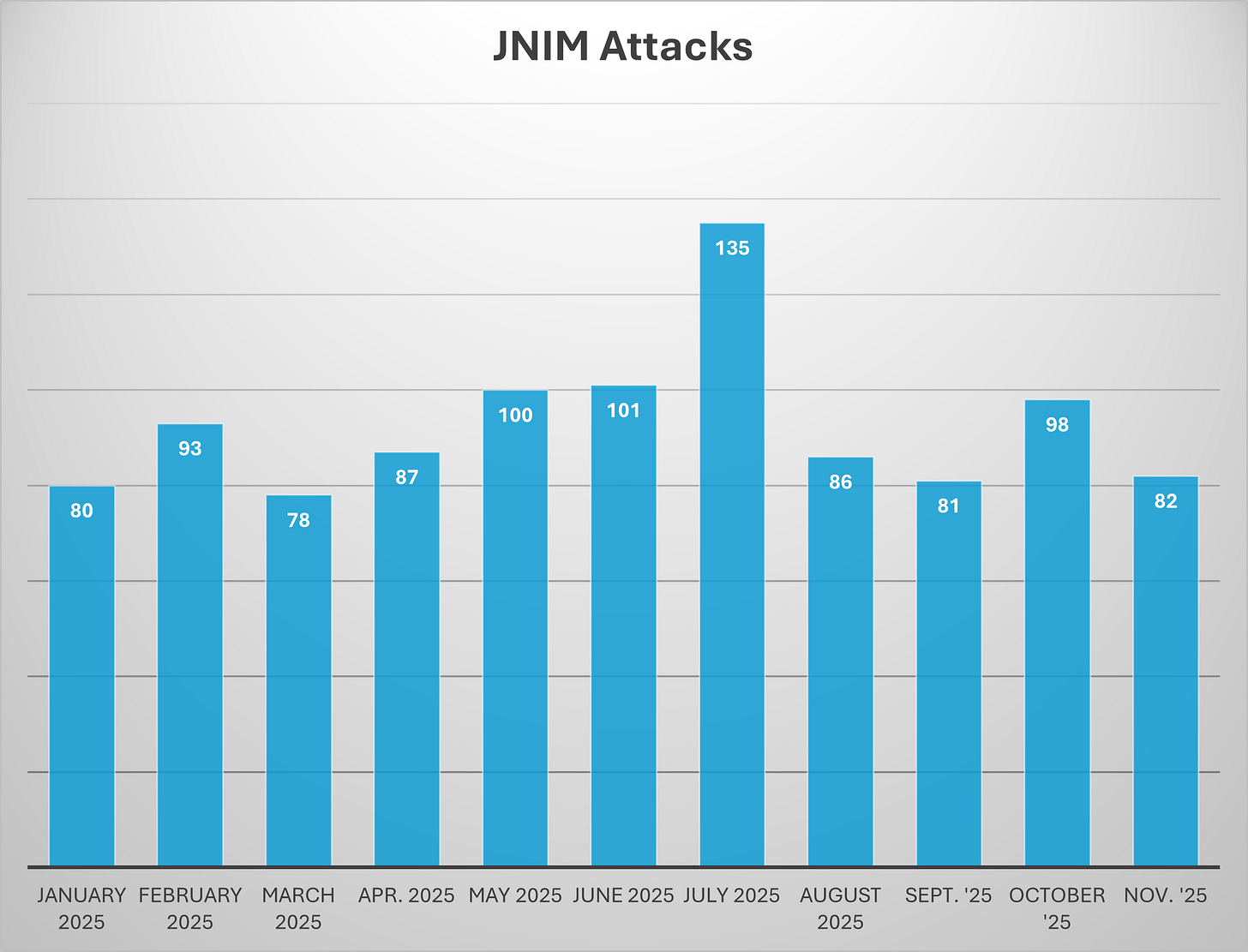

Number of attacks in November 2025: 82

All the attacks were followed by extensive propaganda. In particular, JNIM published 57 statements claiming responsibility for the 64 attacks carried out, along with 69 photos and 4 videos documenting their achievements. As of June 23, Az-Zallaqa Media introduced a completely new look, new colours and new photo backgrounds for its videos, statements and photos. Over the past three months, JNIM has also been using al-Fatah Media, which uses local languages, to disseminate videos.

Targets:

JNIM’s military objectives this month have been many, and they are as follows:

Malian army (FAMa), Malian Dozo militia, Russian PMC Africa Corps, Burkinabè Army, Nigerian Army, Niger Army, VDP militia.

Area:

JNIM hit the following countries this month:

MALI: Mopti region, Timbuktu region, Kayes region, koulikoro region, Kidal region, Sikasso region;

BURKINA FASO: Loroum province, Koulpélogo province, Mouhoun province, Gourma province, Boulgou province, Sanmatenga province, Yatenga province, Poni province, Séno province, Sissili province;

NIGER: Tillaberi region;

NIGERIA: Duruma area, Kwara State.

Conclusion: Security Threat Assessments

Al-Qaeda’s Sahelian affiliate continues to show remarkable military resilience and a growing capacity for regional operational projection. In November 2025, despite a slight decrease in the number of attacks compared to October, the quality of JNIM operations, in terms of tactical complexity, coordination, and the use of new tools, increased. The visual documentation released by the group (operations, training, da’wah activities) confirms a stable fighting apparatus, equipped with functional logistics and capable of conducting complex attacks, including nighttime attacks, with increasing use of drones, SVBIEDs, and numerically substantial units.

The emergence of claims and media content originating in Nigeria represents a significant development, as it suggests JNIM’s willingness to open up or at least test new operational spaces beyond the traditional epicentres of Mali, Burkina Faso, and Niger. At the same time, the intensification of attacks on barracks and bases indicates an attempt to erode the residual state presence in peripheral areas and to delegitimise the defence capabilities of national armies and their allies.

The combination of military and, increasingly, “economic” operations highlights a structural fact: state forces and their auxiliaries do not currently seem to have the capacity or coordination necessary to significantly degrade JNIM’s military power.

On the contrary, the group appears capable of maintaining its operational pace, expanding its areas of influence, and consolidating forms of insurgent governance in areas characterised by institutional vacuums.

In the case of Mali, pressure is coming from multiple directions: from the centre, from the south, and along strategic axes that affect mobility, trade, and access to essential goods. However, the hypothesis of an advance on Bamako, although often evoked, is not consistent with the strategic logic of the JNIM. A direct attack on the capital would have an enormous political cost and would risk catalysing a unified international response, nullifying years of gradual accumulation of local power.

The group’s objective appears more subtle: to build legitimacy in areas where the state is absent, to present itself as a provider of order and justice, and at the same time to accumulate political capital that will be useful in any future negotiations. JNIM seems to be pursuing a hybrid trajectory typical of protracted insurgencies: consolidating territorial control through coercion and minimal services, while working towards a progressive self-representation as a political-religious actor.

In this sense, the JNIM threat is no longer solely military. It is becoming, and in many areas already is, a political threat: a process of de facto institutionalisation of violence that directly challenges state authority and foreshadows a lasting shift in the balance of power in the Sahel.

Intelligence Assessment and Implications for Decision-Makers

The primary risk posed by Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin is no longer confined to the kinetic domain. While the group’s military capabilities remain significant, the more consequential threat lies in its ability to erode institutional authority and state functionality over time. JNIM’s current campaign is increasingly structured to demonstrate that national authorities are unable to guarantee freedom of movement, secure markets, or ensure the reliable provision of basic services. This form of strategic signalling is designed to weaken public confidence in state institutions and to normalise the group’s role as an alternative regulator of security and daily life, particularly in peripheral and contested areas.

Within this framework, the expansion of economic warfare in 2025 represents JNIM’s most impactful operational innovation. By targeting fuel supplies, transport corridors, and logistics infrastructure, the group has shown that relatively limited manpower can generate disproportionate systemic effects. Fuel interdiction in particular functions as a force multiplier, producing cascading consequences across transportation, electricity generation, education, and urban services. From an intelligence perspective, this approach allows JNIM to impose strategic pressure without overextending its forces, while simultaneously creating conditions conducive to political bargaining and de facto recognition at the local level.

Another critical development is the increasing integration of drone-enabled capabilities into JNIM’s operational toolkit. Even limited use of unmanned aerial systems for intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance has altered the tactical balance in several areas. Drone-supported operations improve target selection, enhance situational awareness, and complicate base defence and convoy protection for state forces. Beyond their material impact, drones also carry a psychological effect, reinforcing perceptions of technological adaptation and operational momentum that can undermine morale among security forces and civilian populations alike.

These trends underscore a structural limitation of current counterterrorism approaches. Containment strategies that rely predominantly on military force, particularly when accompanied by abusive practices or indiscriminate proxy violence, are unlikely to produce durable effects. On the contrary, such approaches have repeatedly been shown to expand JNIM’s recruitment pool, strengthen its social cover, and deepen local grievances that the group is adept at exploiting. Without parallel political correction—addressing governance deficits, accountability failures, and community-level security needs—kinetic pressure alone is likely to remain tactically disruptive but strategically insufficient.

From an intelligence standpoint, several critical gaps persist. There is limited visibility into JNIM’s drone supply chains, including acquisition routes, technical facilitators, modification hubs, and cross-border procurement networks. Similarly, the group’s evolving command-and-control arrangements under sustained pressure—particularly its communications discipline, operational security measures, and dispersion mechanisms—remain poorly understood. Financial intelligence also remains incomplete, especially regarding the relative weight of taxation and extortion versus revenues derived from artisanal mining and trafficking networks. These gaps constrain the ability to anticipate operational shifts and to target the group’s true centres of gravity.

At the same time, a set of early-warning indicators can help anticipate escalation or strategic adaptation. Increased interdiction of fuel and transport along key corridors, particularly the Kayes–Bamako axis and routes linking Mali to Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, should be treated as a leading indicator of renewed economic coercion. A higher frequency of drone-related imagery and operational footage disseminated through official or semi-official propaganda channels may signal further institutionalisation of drone use. Likewise, a rising rate of complex assaults against fixed military installations—combining suicide vehicle bombs, indirect fire, and drone-enabled reconnaissance—would indicate growing confidence and coordination. Finally, evidence of sustained operational activity in Nigeria–Niger borderlands, beyond isolated claims or symbolic attacks, would suggest a meaningful expansion of JNIM’s strategic horizon and warrant close monitoring.

© Daniele Garofalo Monitoring - All rights reserved.

Daniele Garofalo is an independent researcher and analyst specialising in jihadist terrorism, Islamist insurgencies, and armed non-state actors.

His work focuses on continuous intelligence monitoring, threat assessment, and analysis of propaganda and cognitive/information dynamics, with an emphasis on decision-oriented outputs, early warning, and strategic trend evaluation.

Daniele Garofalo Monitoring is registered with the Italian National ISSN Centre and the International Centre for the Registration of Serial Publications (CIEPS) in Paris.ISSN (International Standard Serial Number): 3103-3520ORCID Code: 0009-0006-5289-2874Support my research, analysis and monitoring with a donation here on PayPal.Me/DanieleGarofalo88