Islamic State in Africa — Strategic Threat Outlook | November 2025

Continental Operational Trends, Risk Assessment, and Forecast

Executive Intelligence Summary

Africa remains the primary theatre for the Islamic State’s global operational activity, surpassing the Middle East in terms of attack volume, geographic dispersion, and organisational resilience.

As of November 2025, the Islamic State maintains 5 active provinces in Africa, collectively demonstrating:

sustained operational tempo across multiple and non-contiguous theatres;

adaptive local strategies shaped by distinct conflict environments;

The absence of a unified continental escalation, but persistent multi-node resilience.

Operational activity continues to concentrate in West Africa and the Sahel, while Central, East, and Southern African provinces maintain variable but durable capabilities. No continent-wide surge is observed during the reporting period; however, cumulative patterns indicate a structural and enduring threat with potential for regional spillover and episodic escalation.

Threat level: High

Trend: → / ↑ (stable with expansion potential)

Primary risk areas: Sahel, Lake Chad Basin, Central Africa, Somalia, Mozambique

Time horizon: 3–6 months

Confidence level: Medium–High

Scope and Methodology

This Strategic Threat Outlook is based on:

systematic monitoring of Islamic State propaganda (videos, photos, statements, claims);

reporting from sources in the field;

Integration of OSINT, SOCMINT, IMINT, and Digital HUMINT.

Sources include primary Islamic State media channels, open-source reporting, official statements, and local sources across affected regions.

Limitations

Incomplete or delayed reporting from conflict zones;

exaggeration or omission in group claims;

Propaganda bias and potential disinformation.

Where verification is not possible, this is explicitly noted.

Provincial Snapshots

Islamic State West Africa Province (ISWAP)

Islamic State Sahel Province

Islamic State Central Africa Province (ISCAP)

Islamic State Somalia Province

Islamic State Mozambique Province (ISM).

Overview – Islamic State in Africa

The Islamic State (IS) maintains a structured, resilient, and adaptive presence on the African continent, despite pressure from national and international counterterrorism operations. Africa remains the Islamic State’s main global theatre of operations, both in terms of frequency of attacks and capacity for territorial expansion, recruitment, and propaganda production.

Unlike other contexts, IS affiliates in Africa show a high degree of operational continuity, with the ability to carry out attacks using a wide range of tactics: assaults on villages, ambushes against armed and security forces, complex attacks against civilian and military infrastructure, kidnappings, deliberate fires, destruction of infrastructure, and terror campaigns targeting specific religious and community groups. In particular, systematic attacks against Christian villages and civilians are an almost exclusively African feature of Islamic State-linked jihadism, with a significant intensification observed in recent months.

The epicentre of this dynamic remains sub-Saharan and central-eastern Africa, with particularly worrying developments in the Democratic Republic of Congo and Mozambique, where IS affiliates have demonstrated not only a capacity for sustained violence, but also a growing level of coordination, intermittent territorial control, and integration with local criminal economies. In such contexts, violence is not episodic but part of a strategy of progressive erosion of state authority, exploiting structural fragility, socio-economic marginalisation, inter-community conflicts, and governance vacuums.

On March 20, 2025, the Islamic State officially announced the launch of a new military campaign, called “Burning Camps,” with a stated focus primarily on Africa. The areas of reference include Nigeria, Niger, Cameroon, and Mozambique in particular, but the narrative and timing of the attacks suggest a broader campaign, conceived as a tool for simultaneous pressure on multiple theatres. The campaign is characterised by the systematic destruction of villages, farmland, and subsistence infrastructure to destabilise the social fabric, causing forced displacement and amplifying discontent toward central governments.

The strategy remains consistent with the Islamic State’s operating model: creating chronic instability, delegitimising the state, presenting itself as an alternative (or inevitable) actor, and exploiting chaos to facilitate recruitment, logistical support, and territorial entrenchment. In this sense, IS does not aim exclusively at permanent territorial conquest, but at fluid and opportunistic control, sufficient to maintain freedom of manoeuvre and offensive capability.

Currently, the Islamic State is actively and continuously operating in at least eight African countries, with monthly variations in geographical distribution and intensity of activities. During the period under review, the organisation has demonstrated its ability to concentrate its efforts in a smaller number of theatres without losing overall capacity, a sign of a decentralised but functional structure.

A central and often underestimated element is the propaganda dimension. Every significant attack has been followed by intense media activity. In the month analysed, the Islamic State disseminated a significant volume of content—photographs, videos, and press releases—through its central channels, in particular the Amaq news agency and the weekly al-Naba. Propaganda is not limited to claims of responsibility but constructs a narrative of success, resilience, and inevitability, aimed at both local supporters and a global jihadist audience.

In summary, the African picture shows an Islamic State that is not in decline but in a phase of adaptive consolidation, capable of absorbing losses, reorienting priorities, and exploiting the structural weaknesses of local contexts. For intelligence, security, and political and military decision-makers, Africa is not a secondary front but the current centre of gravity of the threat posed by the Islamic State.

Islamic State Activities - November 2025

In November 2025, Islamic State activity in Africa showed a clear dynamic: increased pressure in Mozambique and the Great Lakes region (DRC), while in the Lake Chad basin, ISWAP continued to alternate between “classic” insurgent tactics (attacks/ambushes and attrition of state forces) and intra-jihadist power struggles (competition with Boko Haram/JAS), all supported by a high propaganda output and operational messages calibrated to influence perception, recruitment, and deterrence. In Mozambique (Cabo Delgado), evidence gathered by monitoring systems indicates a month characterised by extensive tactical mobility and persistence in multiple districts, with incidents suggesting a combination of objectives: intimidation of communities, fueling displacement, and seeking logistical depth. Islamic State Mozambique (ISM) remained active in seven districts, with units returning and redeploying between coastal and inland areas and with a renewed capacity to penetrate symbolic centres (including the reappearance of militants in Mocímboa da Praia) in the absence of significant resistance in some cases. In the same month, incidents consistent with a strategy of coercive control and “social targeting” were reported, including targeted kidnappings (even against family members of figures within the insurgent galaxy) that reinforce discipline and local deterrence.

On the counterinsurgency front, a typical “pressure-dispersion” dialectic was observed during the period: operations by Mozambican and Rwandan forces generated pressure in key districts such as Macomia, but without (at least in the short term) causing ISM to collapse and reappear elsewhere, confirming its resilience based on local networks, knowledge of the terrain, and ability to reposition itself.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, November 2025 represented one of the most brutal peaks of violence attributed to ISCAP: between November 13 and 19, MONUSCO attributed a series of attacks to the militiamen, with 89 civilians killed in several locations in North Kivu (Lubero territory), including an episode of high symbolic and psychological value such as the assault on a health center linked to the Catholic Church, with the killing of women and the burning of wards; in addition to the deaths, the reported dynamics (looting of medical supplies, fires, kidnappings) describe violence designed not only to strike, but to disrupt essential services, amplify fear and displacement, and undermine confidence in state/international protection.

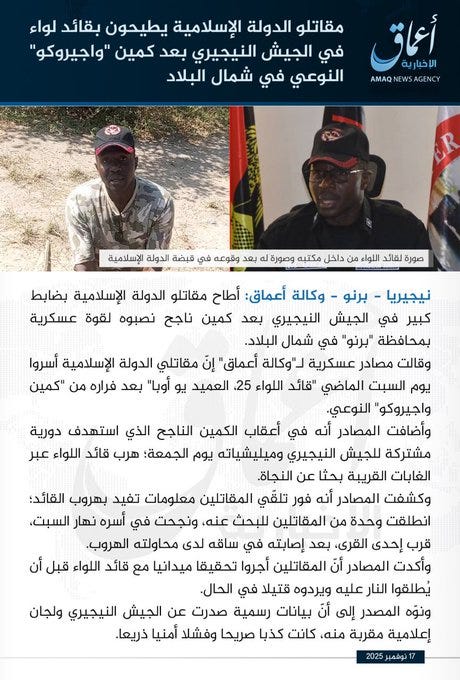

In the Lake Chad basin/northeastern Nigeria, the November 2025 reading must be done in two layers: the “cinematic” layer of propaganda and the “structural” layer of armed competition. On the one hand, ISWAP has sought to impose a narrative of operational superiority through communication (via channels linked to Amaq) by showing that it has captured and eliminated a Nigerian brigadier general. The analytical point is the use of the episode as a deterrent message to the armed forces and as a morale/recruitment lever for the jihadist ecosystem.

On the other hand, friction with Boko Haram/JAS became evident at the beginning of the month: a clash between factions in the Lake Chad area resulted in heavy losses (with estimates in the hundreds among combatants), signaling that the “war between jihadists” remains an operational driver that can temporarily drain resources but also reshape territorial balances and supply chains (boats, lake routes, taxation of coastal communities).

Finally, the broader context of the Sahel continues to provide the strategic backdrop: even when the events of November that dominate media attention are elsewhere, institutional data and warnings confirm that the region remains a global engine of jihadist lethality and state fragility, creating a permissive space in which Islamic State affiliates (alongside al-Qaeda competitors) can capitalize on governance collapses, war economies, and reduced international counterterrorism cooperation.

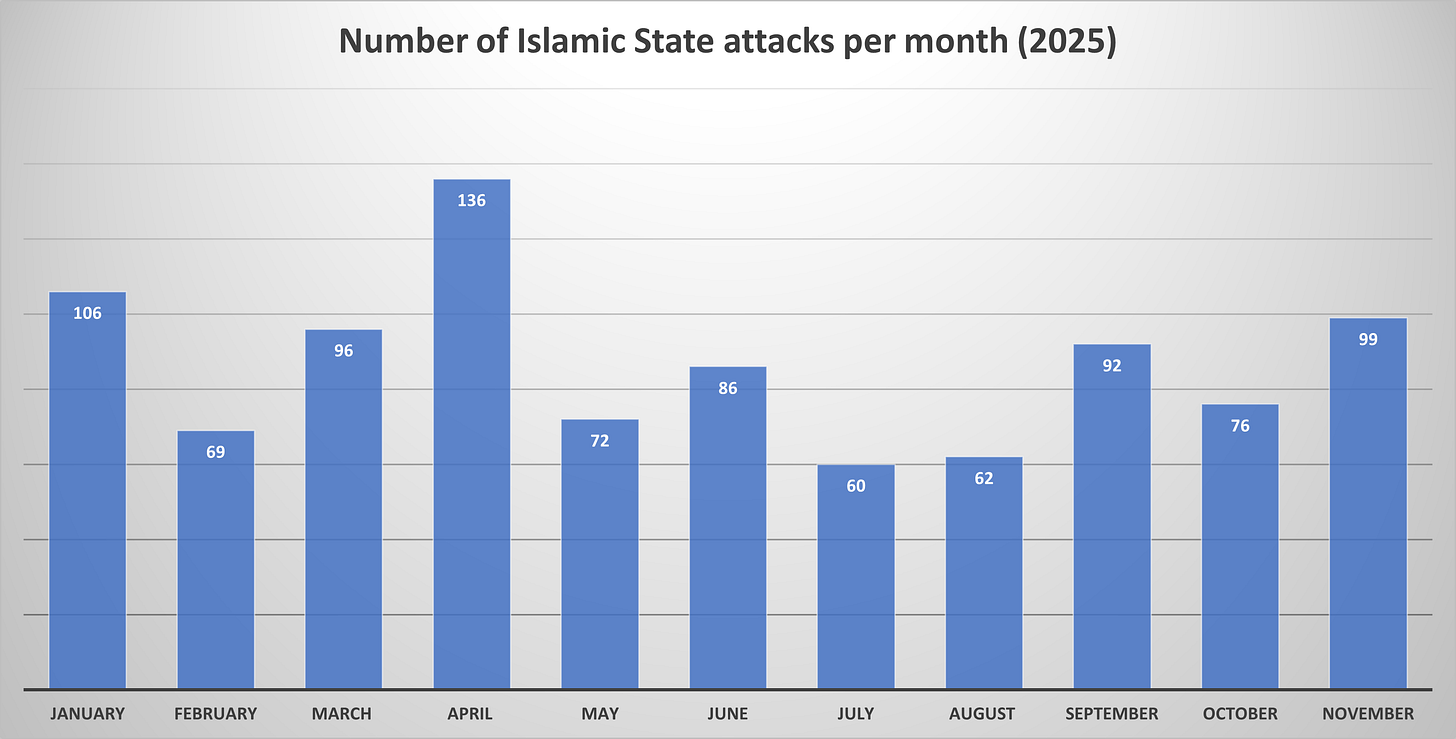

Number of attacks in November 2025: 99

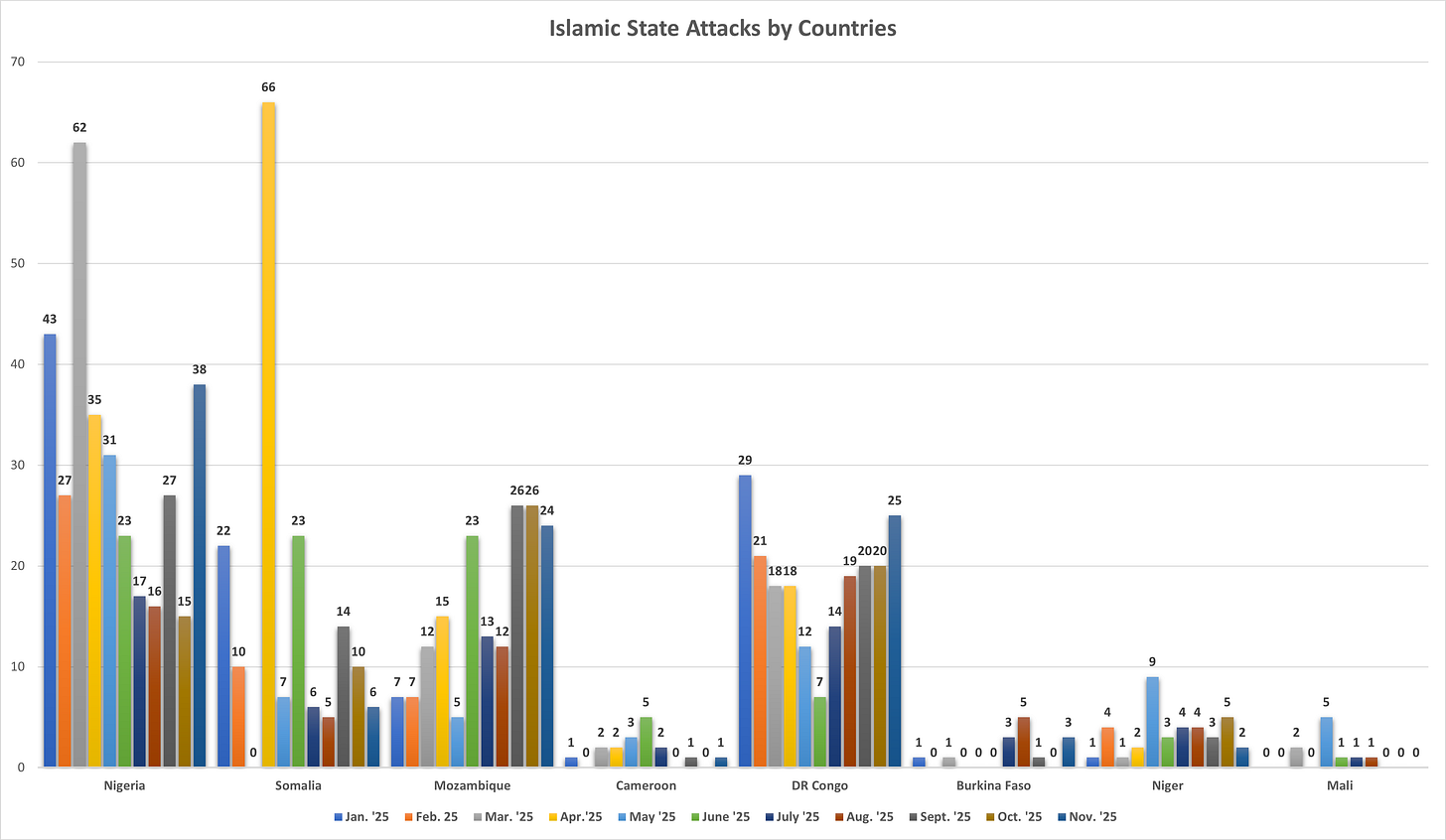

Number of Attacks by Country November 2025:

MOZAMBIQUE: 24

DR CONGO: 25

NIGERIA: 38

NIGER: 2

SOMALIA: 6

CAMEROON: 1

BURKINA FASO: 3

Targets:

IS’s military objectives this month have been many, and they are as follows:

Nigerian Army, Nigerian Police, Nigerian Pro-Government Militias, Mozambican Army, Rwandan Army, Niger Army, Ugandan Army, Congolese Army, Congolese Pro-Government Militias, Cameroonian Army, Puntland Security Forces, JNIM militia, and Christian Civilians.

Area:

The Islamic State hit the following countries this month:

MOZAMBIQUE:

Districts of: Ancuabe, Mocimboa da Praia, Muidumbe, Metuge, Macomia, Nangade; Cabo Delgado Province.

Memba District; Nampula Province;

DR CONGO: Ituri province, North Kivu province;

NIGERIA: Borno State, Yobe State, Adamawa State;

NIGER: Diffa Region;

SOMALIA: Bari region, Puntland;

CAMEROON: Maroua area, Far North Region;

BURKINA FASO: Oudalan province, Séno province; Sahel Region.

Conclusion: Security Threat Assessments

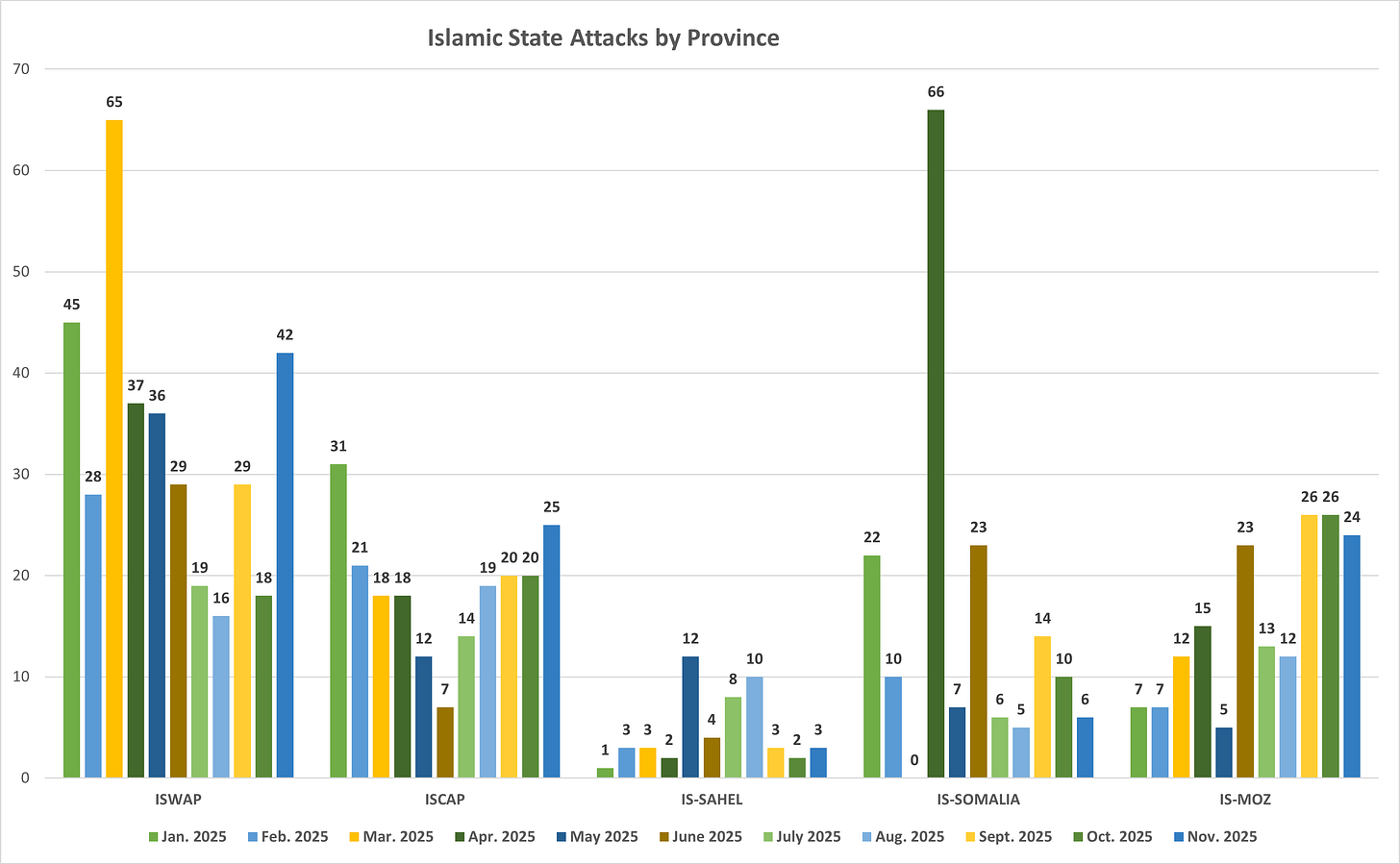

In November 2025, Islamic State military activity in Africa rebounded sharply after October’s decline: 99 attacks compared to 76 in the previous month, an increase of +23 events (approximately +30%). In terms of annual trends, November was one of the most active months of 2025: lower than the peak in April (136) but higher than most months in the second half of the year, confirming a now recurring pattern of tactical fluctuations (a “low” month followed by a recovery) rather than signs of structural collapse. The geographical distribution remains largely stable, with a slight expansion/reactivation of already known areas rather than the opening of new fronts: the threat is “broad” but not chaotic; it is a modular pressure that shifts to where state resilience is weakest or where the organisation sees an operational advantage. The areas most affected during the month were Nigeria (38 events), the Democratic Republic of Congo (25), and Mozambique (24): these three theatres alone account for about 88% of monthly attacks, highlighting a strong concentration of effort on well-established operational hubs (Lake Chad/Borno and surroundings; North Kivu–Ituri; Cabo Delgado). The trend by “province” confirms the hierarchy: ISWAP remains the main generator of incidents (42), followed by ISCAP (25) and ISM (24); IS-Somalia drops to 6 and IS-Sahel remains marginal (3), but this numerical reduction should not be interpreted as an automatic regression of the threat: in 2025, the organization showed that it was able to compensate for the decline in volume with target selection, intensity, violence, and psychological impact. On a tactical level, the month saw a relative decline in “campaign” actions against fixed bases/positions attributable to the “Burning Camps” logic (which also favors destruction and displacement), while two elements remain evident: the persistence of “technical” capabilities, in particular the use of drones and the conduct of night operations (with a specific weight that continues to fall mainly on ISWAP); secondly, the growth of pressure on civilians, with a marked increase in attacks against Christian communities and villages, a dynamic that in Africa takes on a precise strategic function: coercive control of social territory, punishment/disciplining, generation of displacement, and delegitimization of the state. In summary, November does not show an IS “on the defensive”, but an IS that is picking up the pace, concentrating its efforts on three main theatres, and maintaining sufficient adaptability to remain offensive even when some provinces (Somalia in particular) are under greater pressure from counterinsurgency.

Intelligence Assessment (judgments, implications, indicators)

Analytical assessment: The snapshot for November 2025 indicates that the Islamic State in Africa is operating according to a logic of operational time management (time–space–propaganda) rather than simply “number of attacks.” The jump from 76 to 99 events suggests that October served as a repositioning phase (logistical regeneration, reconnaissance, target selection, cell reorganisation) rather than a lasting effect of counterterrorism pressure. The high concentration in Nigeria–DRC–Mozambique indicates that the organisation is investing where it gets the best cost/benefit ratio: contexts with fragmented security, governance gaps, scope for taxation/extortion, and the possibility of projecting violence against civilians with a low probability of timely interdiction. In Nigeria (ISWAP/ISWAP-linked), the persistence of tools such as drones and night-time actions is not a detail: it is an indicator of tactical maturity and a “learning cycle” that is tending to stabilise. For military decision-makers, this means that the threat should not be treated as mere rural guerrilla warfare, but as an actor attempting to gain temporary local superiority (including psychological) and degrade response capabilities. In the DRC (ISCAP/ADF) and Mozambique (ISM), the balance between attacks on security forces and violence against civilians suggests a priority objective: to engineer instability and make displacement endemic, because displacement is an accelerator of recruitment, a way to break “resistant” social networks, and a multiplier of the criminal economy (from predation to route control). The reduction in numbers in Somalia does not imply a “crisis”: more likely, it indicates kinetic and intelligence pressure forcing the actor to reduce visibility and frequency, prioritising survival, internal security, and selective actions. In these contexts, the risk is the classic mistake: mistaking silence for defeat, when often it is only a change in operational profile.

Short-term projection (4–8 weeks): if no external shocks occur (large-scale operations with a persistent effect, targeted logistical disruption, significant internal fractures), the most likely trajectory is a medium-high level with possible localised peaks in one of the three main theatres. The variables to monitor that anticipate escalation are very practical:

1) increase in coordinated night attacks and hit-and-runs in Borno/Lake Chad;

2) repeated raids on villages with systematic burning and blocking of local corridors (DRC/Moz);

3) growth of faster and more polished “post-attack” propaganda, often related to pre-planned operations;

4) signs of more frequent acquisition/use of UAVs or adapted ammunition;

5) increase in targeted kidnappings (children/family members, local authorities, healthcare/humanitarian staff) as a means of control.

Implications for travel security and asset protection: the key data is not just “how many attacks”, but where and with what intention. Nigeria, DRC, and Mozambique remain the theaters with the most unfavourable combination of frequency, local unpredictability, and risk to civilians. In peripheral contexts (Niger, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Mali, in your dataset), the numbers are lower, but the threat can materialise with high-impact events because the presence is often cellular and opportunistic: asset protection must consider time windows, road movements, compound exposure, and predictable routines.

In conclusion, the transition from October to November 2025 reinforces a clear operational message: the Islamic State in Africa controls the pace of violence more than it suffers from it. For intelligence, security, and political and military decision-makers, risk management must therefore be based less on monthly attack counts and more on interpreting fluctuations as an integral part of the adversary’s strategy. Where the number rises, the risk is obvious; where it falls, the risk often changes form, but does not disappear.

© Daniele Garofalo Monitoring - All rights reserved.

Daniele Garofalo is an independent researcher and analyst specialising in jihadist terrorism, Islamist insurgencies, and armed non-state actors.

His work focuses on continuous intelligence monitoring, threat assessment, and analysis of propaganda and cognitive/information dynamics, with an emphasis on decision-oriented outputs, early warning, and strategic trend evaluation.

Daniele Garofalo Monitoring is registered with the Italian National ISSN Centre and the International Centre for the Registration of Serial Publications (CIEPS) in Paris.ISSN (International Standard Serial Number): 3103-3520ORCID Code: 0009-0006-5289-2874Support my research, analysis, and monitoring with a donation here via PayPal.Me/DanieleGarofalo88